Brenda Portman (b.1980) is Organist at Hyde Park Community United Methodist Church in Cincinnati Ohio. In addition to a growing number of organ compositions, she has written numerous concert settings of hymns for solo voice and piano. Fanfare, Chorale and Exultation was commissioned by Village Presbyterian Church in Prairie Village, Kansas, for their 75th anniversary in 2024. The work was premiered in March 2024 by the church’s Associate Director of Music and Principal Organist, Elisa Bickers. The opening section, “Fanfare” incorporates fragments of the hymn tune AURELIA (“The Church’s One Foundation”), which was sung on the first Sunday of the congregation’s history in 1949. However, Brenda Portman disguises these fragments somewhat, for instance by omitting the first note of a phrase and changing its mode. In the “Chorale” section, fragments of “How Shall I Keep from Singing” can be heard quite clearly. The final section is a toccata in which the first hymn tune is gradually reintroduced, in more recognizable form.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) spent most of his short career performing in Europe’s major cities, including Milan, Paris and Vienna, with the hope of obtaining a prestigious position as court composer or music director. Mozart’s freelance activities as a keyboard player involved performances of his piano sonata and concertos. Recent biographies by Piero Melograni and Maynard Solomon contain very few references to Mozart’s activities as an organist, despite a brief formal appointment as court organist to Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Joseph Franz von Colloredo in Salzburg from 1779 to 1780. He wrote only a handful of organ works for the self-playing organ at Count Joseph Dehm’s wax museum in Vienna.

Yet the 18th century was a period of great experimentation in organ building in Austria and Southern Germany, from the instrument built in 1706 by Johann Christoph Egedacher which Mozart knew at Salzburg Cathedral, to the Johann Nepomuk Holzhey organ in Neresheim Abbey, in Bavaria, built in 1797. These instruments feature numerous colorful flute and strings stops at 8 and 4 foot pitch, with a smaller number of reed stops. Although the written repertoire for these organs is slight, consisting mostly of easy pieces similar to the mechanical clock works of Haydn and Beethoven, a recent YouTube video in which Cristoph Bossert demonstrates the Neresheim Abbey organ, shows how effectively a more skilled church organist might have improvised in classical style, at various points of the liturgy.

It is with this background that I have made my own arrangement of the first movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 38 in D major, K.504, premiered in Prague in 1787. Mozart begins his Prague Symphony with a brooding slow introduction followed by a nimble-footed allegro which is characterized by a greater intensity in the development of musical themes than in earlier symphonies. The development section contains sophisticated contrapuntal imitation, and there are numerous subtle details, such as the way Mozart concludes the bridge section in the exposition with a short four-note motive which immediately becomes the main motive of the secondary theme group.

John Scott Whiteley (b. 1950) served as organist at York Minster in England from 1975 until 2010, when he retired to pursue a career as a freelance organist, composer and musicologist. He studied at the Royal College of Music in London, and with Flor Peeters in Malines, Belgium and Fernando Germani in Siena, Italy. He has made numerous solo recordings, including the complete organ works of Joseph Jongen. He also appears as accompanist on more than 20 recordings. He is a prolific composer of organ works and sacred choral compositions. The Passacaglia, Opus 17 (2009) was composed in memory of Diana, Princess of Wales. The first two notes, D – A, spell the first and last letters of her name. Whiteley marks very specific registrations in the score which can be rendered quite effectively on this instrument by Moller/Foley-Baker.

Blind from birth, Louis Vierne (1870-1937) followed the path taken by many other blind French musicians of his day, beginning his musical training at the National Institute for the Blind in Paris, before perfecting his skills at the Paris Conservatoire. Vierne was appointed organist at Notre-Dame Cathedral in 1900 and held this post until his death in 1937. His six organ symphonies continue the symphonic tradition established by his teachers César Franck and Charles-Marie Widor, in exploring the rich tonal palette of the instruments of the Parisian organ builder, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. In his memoirs, Vierne talks about his experience as a student in Widor’s organ class, in which they analyzed symphonies from the German symphonic tradition, including Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, as models for improvisation.

Vierne’s Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Opus 20, was composed between 1901 and 1903. Vierne dedicated the work to Charles Mutin, who became director of the Cavaillé-Coll firm after the death of its founder in 1899. Claude Debussy attended a partial premiere of two movements of the symphony, performed by Vierne (featuring the Choral and Scherzo) at the Schola Cantorum in Paris and remarked, “Old J. S. Bach, the father of us all, would have been very pleased with Monsieur Vierne.”

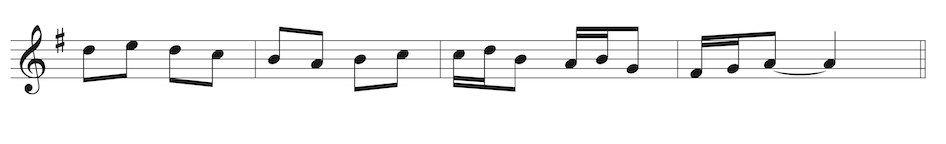

Symphony No. 2 is the first of Vierne’s symphonies to employ cyclical principles, in which the two main themes of the first movement reappear in various guises in the remaining movements of the work. The first movement is cast in sonata-allegro form and opens with a stoic theme featuring dotted rhythms.

Theme A

It is contrasted with a lyrical secondary theme featuring the foundation stops of the Grand Orgue and Positif with the power of the full Récit often buried behind a closed swell box.

Theme B

The second movement reflects the late 19th century interest of French organists in the German Lutheran chorale tradition and the choral-based organ works of J. S. Bach. The main theme (Theme C) is a “chorale” but very much in French romantic style, with precedents such as the 3 Chorals of Vierne’s mentor, César Franck. It is based on a rhythmic transformation of Theme B.

Theme C

The form is basically a five-part rondo with elements of development and recapitulation. Theme C is contrasted with an “agitato” theme which ultimately builds to full organ, at which point Theme C returns in augmentation in the highest voice.

The third movement is arguably Vierne’s most cheerful and lighthearted scherzo, reminiscent of similar movements in Mendelssohn’s string quartets and chamber music. It is also in rondo form, with the first theme being new, and the second theme (Theme D) only loosely based on Theme A, largely in its use of whole or half steps.

Theme D

However, Theme D later reappears as the main theme of the fifth movement (Theme F), which is also cast in sonata-allegro form.

Theme F

The fourth movement, Cantabile, is cast in large ternary form and features a lyrical solo for the clarinet or cromorne. Its main theme (Theme E) retains only a slight connection to Theme A in its use of dotted rhythms and a characteristic descending half-step.

Theme E

However, it is preceded by a four-measure introduction, which in the central development is the only theme that is featured. Theme E does not reappear until the recapitulation.

The final theme to be introduced in Vierne’s symphony is Theme G, which is the secondary theme of the final movement. It is a transformation of Theme A.

Theme G

With the intricate structure of this symphony, Vierne achieves a work which is truly a concert piece, in contrast to his first symphony, written four years earlier, which still feels close to a suite with baroque elements (it opens with a prelude and fugue). Nevertheless, in the second symphony, the serious character of Movements 1, 2 and 5, the registrations Vierne specifies in those three movements, and the evocative use of a chorale in the second movement still give this piece the ethos of church music, while the Scherzo and Cantabile reflect 19th century chamber music traditions.